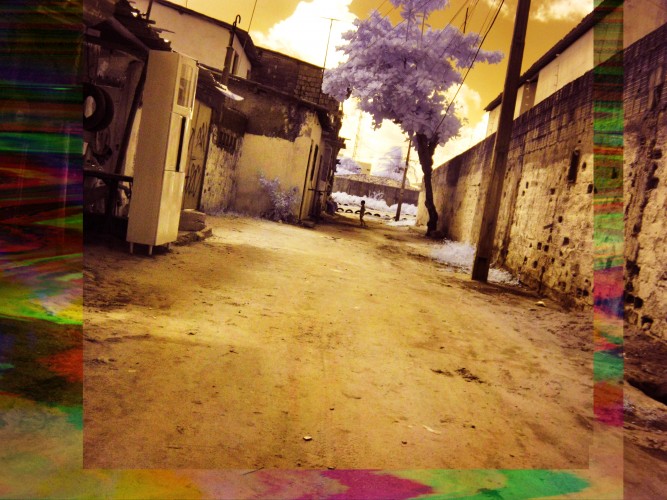

The road.

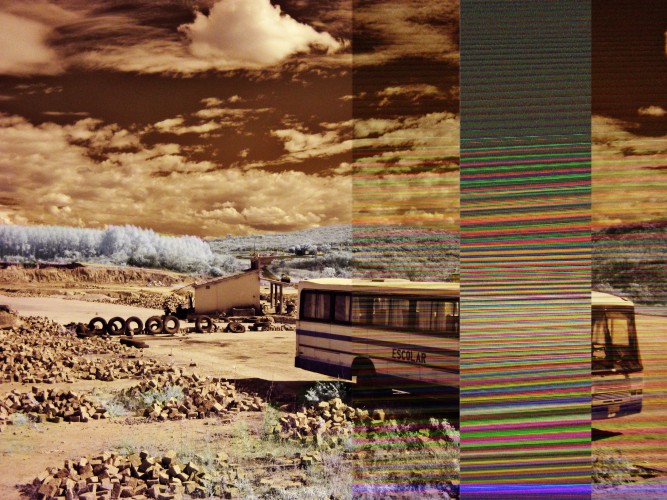

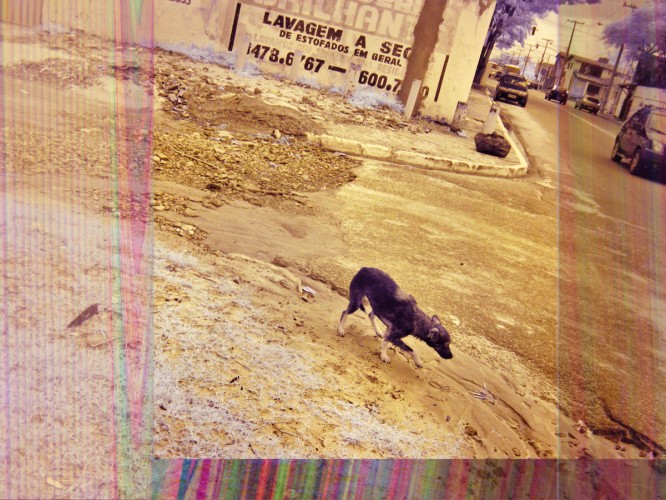

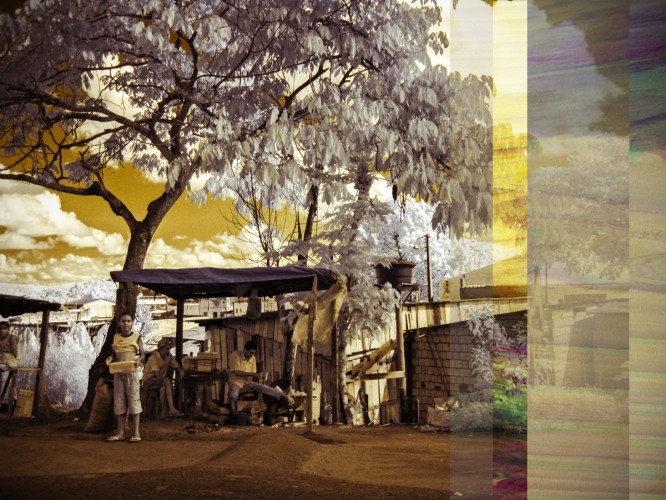

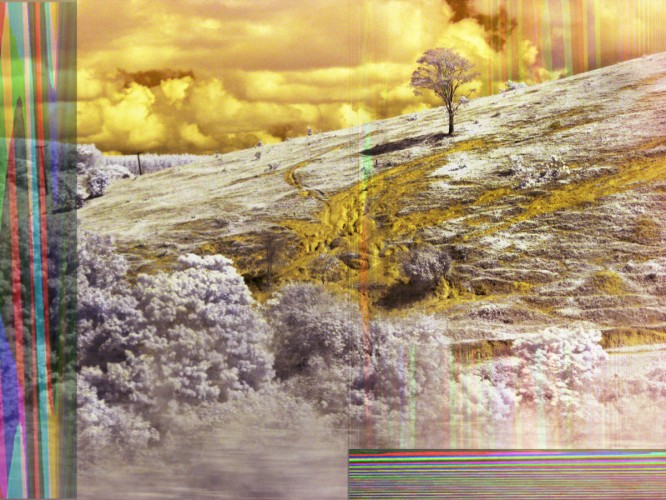

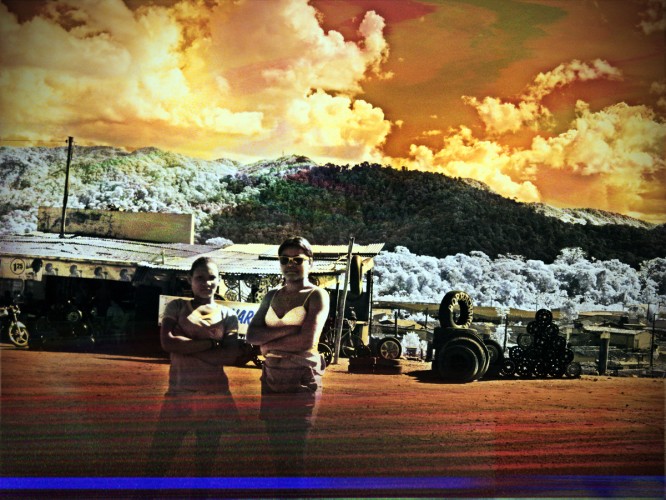

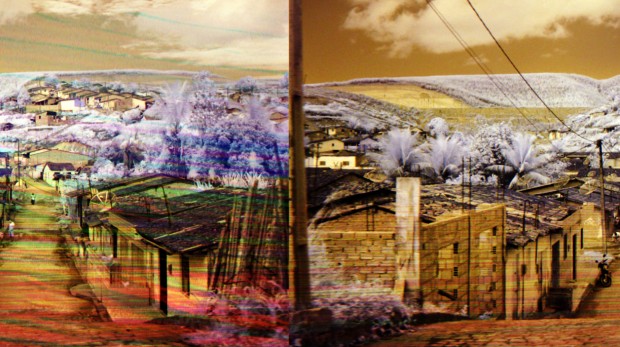

This project, shot on a tiny IR camera in Brasil and edited during a long immigration process in the USA, is both a longing for and visualization of home; a lesson in learning to re-define the term itself. The disorienting intensity of the images is a reflection of the atrocities I had become accustom to witnessing while working with enslaved and abused populations. The static is representative of acculturation; those days when it feels like you’re nowhere and everywhere at the same time, when you question reality itself – a journey to Zion. Zion symbolizes a longing by wandering peoples for a safe homeland. This could be an actual place, a spiritual inheritance, or peace of mind in one’s present life. It was said that God Himself rested on this ancient mountain. The Jewish longing for Zion started with the deportation and enslavement of Jews during the Babylonian captivity. The term Zion was later adopted as a metaphor for deliverance by Christian slaves in the United States. Many psalms of deliverance were written by King David on the ancient mountain of Zion, and many of these psalms were later sung by slaves on plantations in the south.

Though society at large now acknowledges the horror of the slave trade, we have neglected to realize the millions of slaves that exist in other forms. They are victims from every race, every culture, every age group and every socio-economic background. They still exist in our own neighborhoods, schools, our streets. They are still stripped of their futures, dignity, dreams, and their voice. They are still treated without human rights, they are still bought and sold all over the world. Forced to leave their homes and families, carried across borders in boats, cars, planes. There is a small network to help them escape if they are so brave as to attempt it, but by large the message of freedom has not risen up to light the path for those trapped by fear and abuse. Just like the Underground Railroad was a network of safe homes, these victims are also in need of safe homes. Separated from country and family, some need to be placed in hiding upon escape, and others simply come to accept this lifestyle as their fate. No one attempts escape without hope. Harriet Tubman said, “I could have led many more to freedom had they realized they were slaves”.

These photos are an outline of a symbolic mount Zion, and literally – pictures on a map spanning the distance from Goiania in central Brazil to Recife in the northeast. There are 73 of them, one for each psalm written by King David himself; for many suffer in silence, and many receive from silence the answer to their questions. The route they document across the interior of Brazil was a six-day drive taken to open a safe house for rescued children. The images which came from the journey are like pebbles left along the trail for others to find their way home. Like stones, they are a silent testament of unheard cries and muted suffering; objects containing in their parameters stories never told, songs never sung, dreams never lived and the potential for others to pick up the trail. Hope that within the chaos is a still small sound, a voice that never stops encouraging those who risk everything to find home. The route we drove is the same route over which thousands of women and children are transported across the country. Hidden in trucks and busses, sold at stops and brothels like cargo. In a small way I like to believe we began re-writing history along this road, what is currently a pathway to hell will become a map to freedom. What I found along this interstate, buried within the deafening silence of war torn lives, were moments of beauty with which I could not argue, a landscape of promise completely outside my wildest imagination. As my ability to wrestle with questions of suffering slipped away, I found Zion. Inside myself, a hand that reached through the static and reminded me that this story was so much more than the course of my own life, it was a map for all who would follow.

The story (by Michelle Park – Exodus Cry).

From about 1600 to 1850, some 4.5 million enslaved Africans were taken to Brazil; this is ten times as many as were trafficked to North America and far more than the total number of Africans who were transported to all of the Caribbean and North America combined. The enormity of the slave trade’s foothold in Brazil was so far-reaching, that the nation largely failed to develop an effective anti-slavery movement, even while many other nations around the world were making revolutionary reforms. An estimated 38.3 percent of the population of Rio de Janeiro was comprised of slaves. Throughout the 1700s and early 1800s, slavery was being weeded out in the British Empire, North America, and France. Brazil, however, still had nearly one and a half million slaves with the number of slave imports only accelerating.

Finally in the late 1800’s young lawyers, students, and journalists started to urge their fellow Brazilians to follow the example of the liberation of the slaves in North America. In 1873 Joaquim Nabuco began his fight against slavery in Brazil. The struggle for total abolition kept moving forward under his leadership, and finally on May 13, 1888, the imperial family passed Lei Aurea, “the Golden Law”, making Brazil the last nation in the Western Hemisphere to formally abolish slavery. Even after the slave trade was abolished, years of exploitation continued to have profound effects on Brazilian society, including deep social divides and the widespread expansion of prostitution. Ever since the late 19th century, prostitution has been “part of the cultural landscape in the early period of Brazil’s modernization and urbanization, as slave or ex slave women turned to offering sexual services” for survival. Such long-standing slavery in Brazil created a vast lower class and extreme inequalities.

Today, just one hundred and twenty-five years after slavery was abolished, Brazil still faces the repercussions of its near 400-year human trafficking legacy. There is an urgent need for resurging abolition efforts to combat a battle that has moved from the brutality of plantation life to brutality in the streets. The extreme economic inequalities give children and teens no other choice but to find work wherever they can. Ripples of ancient systems and dehumanization still linger across Brazil, yet when we look at Brazil’s history, we see that abolition proves to be an inevitable force. It is a story that prevails, with heroes that continues to rise up even in the harshest of circumstances.

Today, just one hundred and twenty-five years after slavery was abolished, Brazil still faces the repercussions of its near 400-year human trafficking legacy. There is an urgent need for resurging abolition efforts to combat a battle that has moved from the brutality of plantation life to brutality in the streets. The extreme economic inequalities give children and teens no other choice but to find work wherever they can. Ripples of ancient systems and dehumanization still linger across Brazil, yet when we look at Brazil’s history, we see that abolition proves to be an inevitable force. It is a story that prevails, with heroes that continues to rise up even in the harshest of circumstances.

The songs (by Ray Hughes, The Minstrel Series).

Slaves working on plantations in the United States were not allowed to talk while they worked. But they were allowed to sing. Singing boosted moral. They worked faster while they sang. They were more productive when they sang. These melodies were spiritual songs that told of a better existence; a spiritual realm where suffering didn’t exist, where freedom was complete and for all. The songs of the slaves were so beautiful that some were even appointed as “coon singers” and made to sit outside of the master’s house all night to serenade the family until dawn. The fields were filled with spontaneous song from morning till night, and that was just fine with the plantation owners. The cadence and the rhythm of the slave’s melodies kept them steady and kept them focused. Each morning, one man would take the role of a “line captain”, who would set the tempo and lyric of the day. However, what the masters didn’t know is that the directions to the Underground Railroad were encoded in the lyrics of many of these hymns. The white man let him sing these “silly tunes”, but what he didn’t know, is that the slaves were continually singing the directions to their freedom along a an unmarked trail leading north. All on the plantation were well aware of this road. The instruction would be sung out in code, when escape parties were arriving, where to meet, when to go. The roadmap to deliverance was auditory, verbally painted, and available for all who risked their lives to access it.

While some of these songs were literally directional, others were deeply spiritual and focused on another type of freedom. Many of the hymns sung in the fields were taken from the psalms. The psalms –are a legacy of the Old Testament. These 150 Chapters recount both times of great suffering and great reward. For 24 hours a day musicians were brought to Zion where a 4000-piece orchestra was established to accompany the lyrical hymns. Prior to this, there was no musical worship in the temple. Even more contrary to the cultural norm of the day, animal sacrifice was banned during this 33 year period before the exile. It was in fact the prophetic enactment of a new day when a savior would give his own life to set men free. Centuries later, Christ’s life span would last exactly 33 years. Zion was called the resting place of God. It was a geographic location and simultaneously a model of the kingdom of heaven on earth in which all suffering would cease. This mountain was a place of pilgrimage for tribes and cultures from all over the earth; it was a light on the hill, a place of deliverance, freedom, and safety. Zion was later captured in war but what was established there remains in song and legend. As the spiritual reality of Zion, transcribed in David’s psalms becomes part of a people’s manifested expression, they rise like a light on the mountain illuminating the pathway to freedom, just as slaves once sang the directions to the Under Ground Railroad throughout the fields.